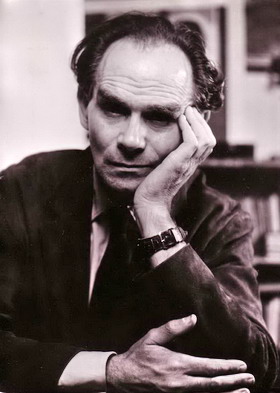

Bálint, Endre (1914-1986)

He studied poster designing at the School of Applied Arts from 1930 to 1934, then attended the private school of János Vaszary and Vilmos Aba Novák. From 1936 he spent several summers in Szentendre, in the company of his friend Lajos Vajda and the young artists gathering around him. In 1945 he was a founding member of the artist group called European School. The motifs crammed within thick, dark contours and strained in an instable and hectic composition testify to the intention of an expressive rewriting of the sight before his eyes. From 1945 onward he painted recollections of the war with powerful gestures. In 1947 he witnessed as a participant the second surrealistic world expo in Paris. Impressed by this event, his paintings of the end of the 40s and the beginning of the 50s became populated with imaginary creatures: elves, kobolds and anthropomorphic organic creatures.

While passing through a crisis as an artist in the middle of the 50s he consciously groped for Vajda's transparency methodology. These drawings - that eventually take him to setting his imagination free - already show the typical motifs of his later art mounted one on the other: a horse-headed mouse, wheel-forms, fragments of Swabian and Arabic female figures. After periods of staying temporarily in Paris, he lived in France continually from 1957 to 1961. In 1958 Édition Labergerie published the Jerusalem Bible with more than a thousand of Bálint's illustrations, and this helped him in developing his typical late artistic style. From 1959 onward he painted one after the other his most valued paintings, including the Miraculous Fishing (1960), the Dream in the Public Park (1960), I Walked Here Sometime I-II. (1960). These works of art can be classified as the representatives of late surrealism. In them familiar recollection-fragment clichés of nostalgia-imbued childhood and the past, all positioned in never-seen internal landscapes are mingled according to the 'logic' of human dreaming and remembrance with unknown, mysterious and often frightening figures and shapes, in order to become players of a story for which there are no human words to express. At the end of the 60s and the beginning of the 70s the epic nature of this painting is replaced by the depiction of motifs of symbolic value. The elements torn from their original context became the main characters of montages that are more ironical than the paintings and of objects that are often more grotesque than the paintings. His writings and memoirs published in a number of volumes are important sources on the artistic life of his age.

Source: Hungarian National Gallery